Design poker

I believe that embracing randomness is a powerful way to break out of repetitive thinking—after all, with randomness, no one knows what will happen next.

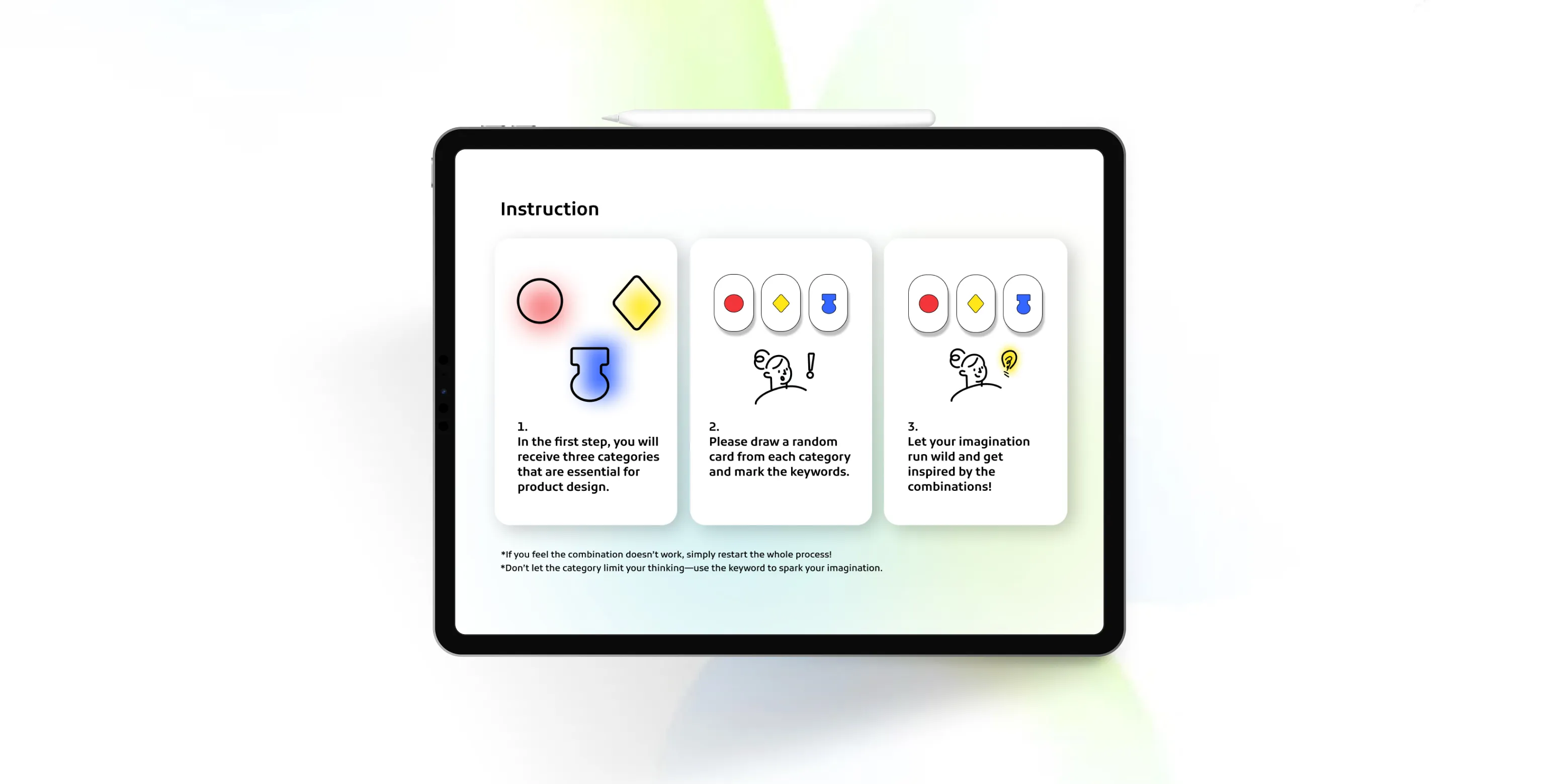

Following a recommendation from Prof. Martin Schmitz, I explored the design method known as

"Design Poker", developed by Andreas Brandolini in 1987.

At the core of the method are six key criteria that Brandolini identified as essential to product design:

Material, Technology, Material Sourcing, Design Motivation, Cultural Background, and Idea Generation.

Each category contains a variety of keywords, which are used to spark unexpected combinations and creative directions.

Next, participants must define their task, which involves selecting an object to design. The following step is: Each "designer" draws a card from each category and attempts to incorporate the components into their design. If there are significant contradictions between the cards, they are allowed to redraw up to two cards.

playing Design poker

Based on this theory and its rules, I created my own set of cards and tested the method several times with friends.

Below are the session logs and observations from these experiments.

To begin the Design Poker session, I asked the group:

“What criteria do you consider most important when designing a product?”

The responses included:Target user group/ Functionality of the object/ Design goals/ Design style/ User needs/ Relationship between the product, the user, and the environment/ Product usage/ Emotional value/ The feeling or experience the product provides/ Innovation/ Materials used/ Product appearance...

It's worth noticing that user needs were mentioned multiple times. Then, the Design Poker game officially began.

We started with the original version of Design Poker.

Here are the three selected objects and the cards drawn for each:

Here’s a summary of the feedback I received from participants during the Design Poker session:

1. Mismatch of materials and techniques:

Some participants felt that the materials and techniques drawn at the beginning didn’t seem to fit together—at least from a subjective point of view. Even if a combination might technically work, many participants chose to redraw cards immediately. Often, they already had a preferred answer in mind before drawing.

2. Lack of unexpected inspiration:

After drawing all six keywords, participants felt they didn’t gain new inspiration. Instead, the keywords felt more like constraints. The categories "Material Sourcing" and "Design Motivation" were perceived as particularly limiting.

3. Creative value increases with repetition:

Several participants suggested that the activity becomes more meaningful and inspiring when repeated. The more often you play, the more creativity and ideas you can generate.

4. Disconnect between keywords:

Many participants noticed that the randomly selected keywords didn’t always relate to one another, which made it difficult to develop a coherent concept.

Summarize the process

Some participants showed little interest in completing the design task, either because they were not inspired by the method or simply felt disconnected from the process.

I believe that Design Poker offers an interesting and playful design challenge. However, it often feels like working on a design challenge with preset constraints.

While these constraints are meant to inspire creativity, in practice they can limit the range of possible ideas and design directions.

However, I found the idea of randomized design to be very compelling. That’s why I wanted to transform this theory into a practical tool that could support designers during the brainstorming phase.

As a next step, I explored several rule variations on how Design Poker could be played, and tested them together with friends.

Rule Variation 1

In this version, no specific object is defined beforehand.

Each participant draws six random keywords—one from each category—and creates a design concept based solely on these keywords.

Feedback from participants:

1. Some keywords were contradictory, making it difficult to form a cohesive concept.

2. Certain keyword combinations described scenarios that were hard to realize or imagine.

Rule Variation 2

In this version, the method is carried out in groups.

All participants agree on one common design goal. Then, one keyword is drawn from each of the six categories.

The group then engages in a collective brainstorming session, exploring ideas and combinations based on these keywords together.

Feedback from participants:

1. The collaborative discussion process was found to be more inspiring than working individually.

2. Some participants expressed a preference for starting with materials or user needs, rather than a predefined object. As a result, the game didn’t fully align with the natural approach of many designers.

3. One participant was reminded of a Steam game called Storyteller, where players build a story using a set of predefined elements. This association suggests that Design Poker could be explored further as a narrative design tool.

Rule Variation 3

In this version, the method is carried out in groups, but with a twist:

Each participant can choose their favorite category from the six available. This means some categories might be repeated, while others might not appear at all.

The selected keywords are then combined and discussed collectively, with the goal of developing a shared design direction based on the spontaneous combinations.

Feedback from participants:

1. No one selected the "Design Motivation" category, as the keywords drawn in the first two rule variations often felt disturbing and didn’t align well with motivational aspects.

2. Cultural motivations emerged as the most frequently chosen category, offering a broader range of possibilities.

3. While this variation provided more options compared to the second rule variation, participants struggled to convince each other, and consensus was difficult to achieve.

Rule Variation 4

In this version, the method is carried out individually.

The participant first defines their starting point for the design, which could either be an object they want to design or a material they wish to use.

Next, the participant selects 2 to 6 favorite categories from the six available. Based on the drawn keywords and starting point, they then engage in a brainstorming session to explore design possibilities.

Feedback from participants:

1. Participant A, who wanted to create a product from "eggshells", selected techniques, material sourcing, and idea generation.

Participant B, who aimed to design a vase, selected motivation, idea generation, material, and material sourcing.

2. During brainstorming, participants often focused more on the meaning of the keywords themselves, neglecting the categories they belonged to. They frequently confused material sourcing with "where do I use my product."

⭐Conclusion and goal

After running all the variations, I gathered the following key insights:

1. When participants had no initial design idea, cultural motivations—which often reflect target audience considerations—were the most important factor for them.

2. When a starting point was provided, participants tended to select different categories based on their individual design goals.

3. Discussing design ideas with others consistently led to more inspiration and broader perspectives.

These findings led me to believe that the best version of Design Poker is one that balances control and randomness. The element of chance can spark fresh ideas, while maintaining a degree of control allows designers to stay aligned with their original intentions.

To achieve this, I decided to develop my own version of Design Poker—one that builds upon the original method, but introduces new rules and structures tailored to support both creative freedom and designer needs.